(Credit: © Irfanbm03 | Dreamstime.com)

In a nutshell

- Astronomers studying the nearby Coma galaxy cluster have found new evidence that the universe is expanding about 9% faster than predicted by our current physics models – a discrepancy known as the Hubble tension. This finding strengthens concerns that our fundamental understanding of cosmic evolution may need revision.

- The research team measured precise distances to 13 supernovae within the Coma cluster, determining it lies about 98.5 million light-years from Earth – significantly closer than the 111.8 million light-years predicted by models based on observations of the early universe. This difference is too large to be explained by measurement errors.

- Multiple independent measurement techniques all point to the same conclusion, suggesting the problem lies not in our observations but in our theoretical models. This indicates that resolving the Hubble tension may require new physics beyond our current understanding of how the universe works.

DURHAM, N.C. — Our cosmic neighborhood is revealing an uncomfortable and unexplainable truth: the universe seems to be breaking the speed limit set by our best physics models. By precisely measuring the distance to a massive cluster of galaxies relatively close to Earth, scientists have uncovered new evidence that space itself is expanding more rapidly than theoretical predictions allow, a finding that could force a radical revision of our understanding of cosmic evolution.

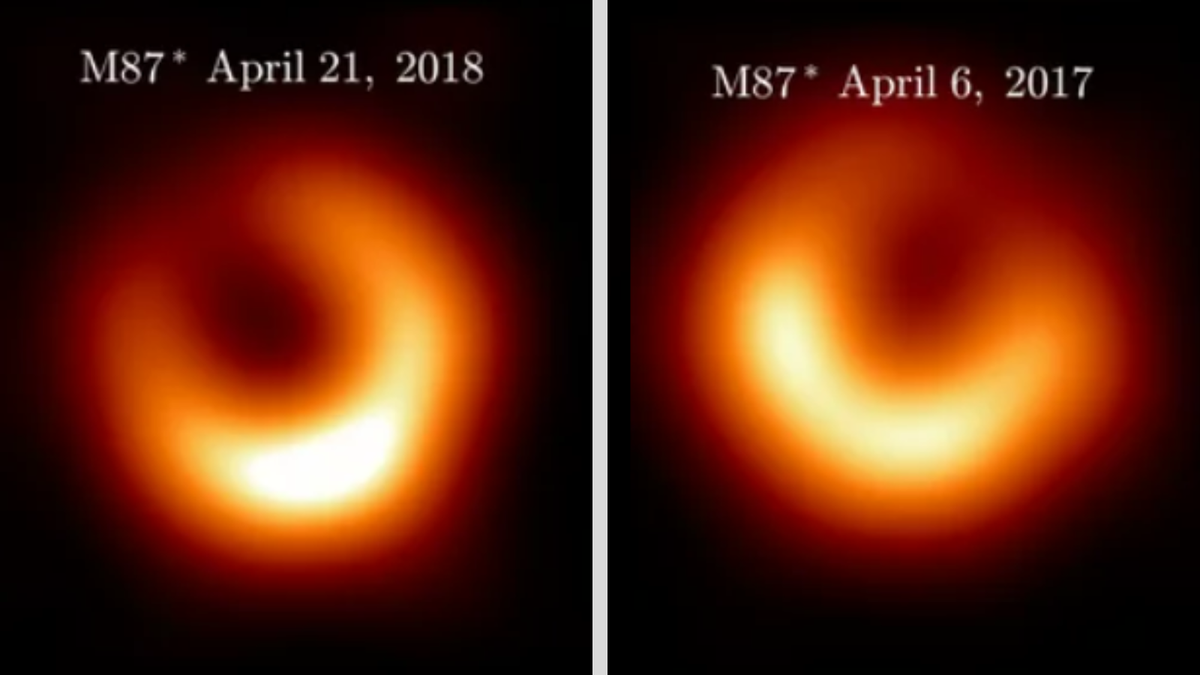

When scientists measure this expansion rate (known as the Hubble constant) using nearby objects, they consistently get a higher value than when they measure it using light from the early universe. This discrepancy has persisted for years, leading astronomers to wonder if our understanding of cosmic evolution needs a major overhaul.

Dan Scolnic, an associate professor of physics at Duke University who led the research, frames the puzzle in relatable terms: imagine trying to create the universe’s growth chart. We have its “baby picture” — the earliest observable state just after the Big Bang — and its current “headshot” showing the local universe containing our Milky Way and neighboring galaxies. The challenge lies in connecting these two points through a coherent growth curve, but the measurements aren’t adding up as expected, deeping one of modern cosmology’s most perplexing puzzles known as the “Hubble tension.”

“The tension now turns into a crisis,” says Scolnic, highlighting the significance of his team’s findings published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

So what exactly is the Hubble tension? Imagine having two reliable methods for measuring the same thing, like a bathroom scale and a doctor’s scale, but getting consistently different results from each. That’s what astronomers face when measuring the Hubble constant. When they use nearby objects like supernovae and galaxies to measure this expansion, they find the universe is stretching at about 73-76 kilometers per second for every megaparsec (roughly 3.26 million light-years) of distance. However, when they calculate the expansion rate using observations of the cosmic microwave background — the afterglow of the Big Bang — along with our standard model of physics, they get a significantly slower rate of about 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

This discrepancy, about 9% difference between the two methods, is far too large to be explained by measurement errors. Even more troubling, as measurement techniques have improved over the years, the disagreement has only become more pronounced rather than resolving itself.

The new study focuses on the Coma Cluster, one of our nearest massive galaxy clusters, serving as a crucial calibration point for measuring cosmic distances. When the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) team published their extensive galaxy observations, Scolnic recognized an opportunity to refine their measurements using the Coma Cluster as an anchor point.

NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA).)

“The DESI collaboration did the really hard part, their ladder was missing the first rung,” Scolnic explains. “I knew how to get it, and I knew that that would give us one of the most precise measurements of the Hubble constant we could get, so when their paper came out, I dropped absolutely everything and worked on this non-stop.”

His team analyzed 12 special stellar explosions called Type Ia supernovae within the Coma Cluster. These cosmic phenomena serve as reliable “standard candles” because they consistently reach the same peak brightness, making them excellent tools for measuring astronomical distances. Much like knowing the wattage of a light bulb allows you to estimate its distance based on how bright it appears, these supernovae enable precise distance calculations.

The results placed the Coma Cluster at approximately 320 million light-years from Earth, aligning well with decades of previous measurements. This consistency provides strong validation for the study’s methodology. “This measurement isn’t biased by how we think the Hubble tension story will end,” notes Scolnic. “This cluster is in our backyard, it has been measured long before anyone knew how important it was going to be.”

Using this precise measurement as a starting point, the team calculated a Hubble constant of 76.5 kilometers per second per megaparsec. This result aligns with other recent measurements of the local universe but conflicts significantly with predictions based on observations of the early universe.

“We’re at a point where we’re pressing really hard against the models we’ve been using for two and a half decades, and we’re seeing that things aren’t matching up,” says Scolnic. “This may be reshaping how we think about the Universe, and it’s exciting! There are still surprises left in cosmology, and who knows what discoveries will come next?”

Moving forward, astronomers will continue refining these measurements using new telescopes and improved techniques. However, the consistency of results across different methods suggests that resolving this cosmic expansion crisis may require more than just better observations – it may demand a complete overhaul of our current physics models.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The researchers identified supernovae within the Coma cluster using publicly available catalogs and light curves. They focused on Type Ia supernovae, which serve as reliable cosmic distance markers due to their consistent peak brightness. The team applied strict quality control measures, analyzing only supernovae with good light curve coverage and spectroscopic confirmation. They used sophisticated modeling techniques to account for various factors that could affect brightness measurements, including dust extinction and observational biases.

Results

The study found that the Coma cluster is approximately 98.5 million light-years away, with a margin of error of about 2.2 million light-years. This measurement conflicts significantly with predictions based on cosmic microwave background observations, which suggest the cluster should be about 111.8 million light-years away. The difference is too large to be explained by random chance or measurement errors.

Limitations

The research team acknowledges several potential limitations, including the relatively small sample size of 13 supernovae and the challenge of precisely determining cluster membership for some objects. They also note that the radial size of the Coma cluster itself (about 2.86 million light-years) could introduce some uncertainty into the measurements.

Discussion and Takeaways

This study provides strong evidence that the Hubble tension extends beyond just measurement techniques and into fundamental aspects of our local cosmic environment. The findings suggest that our understanding of cosmic expansion may need revision, as multiple independent measurement methods consistently show discrepancies with predictions from early-universe observations.

Funding and Disclosures

The research was supported by several organizations, including the Templeton Foundation, the Department of Energy, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Sloan Foundation. The study also utilized data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), which is managed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Publication Information

This study, titled “The Hubble Tension in Our Own Backyard: DESI and the Nearness of the Coma Cluster,” was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on January 20, 2025. The research was led by Daniel Scolnic from Duke University, along with colleagues from various institutions including the Space Telescope Science Institute and Johns Hopkins University.

Leave a Reply